How Do Researchers Measure Animal Behavior Using Their Perspective

People have pondered animal beliefs since the beginnings of human existence (Frison 1998). Insights into animal beliefs allowed our ancestors to outsmart prey during a hunt or befriend another animal, the latter somewhen leading to domestication of animals. Knowledge of animal mating systems helped human being societies grow, considering propagation of domesticated stocks ensured that there were dependable supplies of nutrient (Zeder 2008).

When observing wild or domesticated animals today, we are often fascinated past their persistence in accomplishing a given task, such equally when magpies adjust private sticks to course a nest or when a pet seeks out its favorite toy (Figure 1). And, nosotros go along to ask basic questions about fauna behavior: Do animals have motivations and preferences? Do they make conscious choices? When given culling partners or various foods to cull amongst, do animals brand adaptive choices that are practiced for them? These and similar questions are addressed in controlled experimental designs that measure and test connections between an observed behavior and its hypothesized affectors.

Effigy ane

Pet dogs normally enjoy play and can develop stiff preferences for specific activities and toys.

What are Motivations, Preferences and Choices, and Why Do Animals Take Them?

Motivation, the desire or willingness to engage in a behavior, can exist positive or negative and vary in strength. Motivation is positive for tasks and outcomes that animals wish for and negative for undesirable activities. Positive and negative motivations are inferred from beliefs, for example, from approach-behavior vs. abstention, respectively (Kirkden & Pajor 2006).

Motivational strength varies between individuals. Some components of this variation can be ascribed to abiding individual factors like species-specific characteristics or gender, while others are explained by changing individual or environmental factors like age, experience, fourth dimension of twenty-four hour period, weather condition, and resources predictability. In other words, a motivation is generally influenced by many factors that can be intrinsic (due east.thou., genetic or physiological) or extrinsic (i.e., in the animal's environment). To illustrate, the motivation to potable (thirst) can be increased past hormones responsible for controlling the body's h2o balance, merely is also enhanced by the sight of water.

Preferences are based on an ability to evaluate sets of simultaneously available alternatives that satisfy the same motivation and to aspire toward the one opportunity that is near desirable. A preference may be specific to the individual (such as preferring white potato fries over nuts), and refers to the difference in motivational force to get the one resource over the other, or others. Ultimately, animal preferences are inferred from choice behavior. Choice beliefs refers to what an creature actually does — the consequences of its preferences and its last decisions.

In summary, before animals brand choices they go through a conclusion-making process guided by their motivations and preferences. Presumably, this strategy is adaptive, insofar as being advantageous to the animal and favored past evolution via natural option: Individuals that choose beneficial options, like eating the more than nutritious food or resting at the safer nesting site, are also more than likely to accept offspring that are successful in reproduction and survival (Existent 1991).

How Tin can Nosotros Assess What Animals Prefer and the Forcefulness of Their Preferences?

Information technology is feasible to measure out animal pick beliefs in the wild and make inference about what animals prefer. Jane Goodall, for example, used ad libitum behavior sampling to reveal details about the preferred placement of chimpanzees' sleeping-nests in Tanzania. She found that nests typically were built in rather inaccessible places, presumably every bit a predator avoidance strategy (Goodall 1962). Thus, behavioral information from field studies can provide useful information about fauna choice beliefs, only the results tin can also exist challenging to interpret because many factors that influence behavior are outside the researcher's control.

Many scientists examine animal behavior in standardized test situations in the laboratory. In this setting, behavioral affectors are more hands monitored and controlled for than in the wild. For reliable control over experimental variables and optimal power to exam behavioral affectors, laboratory studies are commonly performed with captive-born or domesticated animals that are familiar with semi-natural or bogus housing situations. In the laboratory, an animal'due south preferences are tested by allowing it to choose between two or more divers options. Side by side, when the creature'due south option behavior reveals the pick that is preferred or avoided in the experiment, the scientist can movement on to ask how potent its behavioral preference is. Such tests are termed motivation tests.

In laboratory testing of factors that can influence beliefs, treatment animals, which are exposed to the gene or factors of involvement, are contrasted to reference observations. In some experiments, the reference observations are made initially to determine the baseline behavior of each animal. After treatment, the creature is compared to its own baseline as a reference or internal control. In other experimental designs, carve up subsets of individuals course a reference or command grouping that parallels the treatment in all aspects other than the factor(southward) of interest. Subsequent comparisons of the command and treatments groups allow scientists to conclude about the influences on behavior, with fewer disturbances from intrinsic and extrinsic elements that tin can confound interpretation.

Example Study 1: Social Preference and Motivational Force

Among dogs, it is important for young animals to collaborate with others for play and social learning, and to feel rubber. The aforementioned is true for other canids including convict silver foxes, known in the wild as the red play a joke on (Vulpes vulpes). At two months of age, fob pups prefer social contact and respond towards both familiar and unfamiliar pups in a playful manner. All the same, as the foxes age from pups to seven-month-one-time juveniles, they spend less fourth dimension with a social companion and their behavior towards strangers changes from playful to ambitious (Akre et al. 2009).

How can we measure whether juvenile foxes are motivated for social contact?

A method for testing an brute's strength of motivation is to ask it to "pay" an archway fee for admission to a resource and and so measure the maximum "price" it is willing to pay. But what sort of currency can be used with animals like foxes? The currency is typically a learned behavior, like pushing a heavy door or pulling a loop string, a so-called operant response. Also, when using operant methodology to test whether social contact is important; the cost foxes pay for access to a companion must be compared with admission to a baseline resource of known importance to them. One such resource is food, since animals are motivated to satisfy their hunger (Jackson et al. 1999). The foxes' valuation of nutrient thereby becomes the internal reference-behavior of this written report.

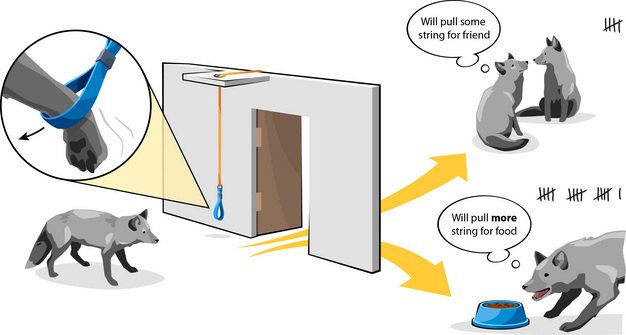

This system (Effigy two) was used to test the strength of social motivations in six juvenile female person silver foxes that had been trained to pull a loop to open a door. When a play a trick on delivered a required number of pulls, the door opened into a chamber. The foxes' motivations were examined in 2 separate trials: During one trial, the foxes worked for food placed within the sleeping room to plant their individual reference value. During the other trial, the foxes could socialize with another female when they visited the chamber. The companion could freely enter or leave, which insured that beingness together was voluntary.

In each trial, the experimenters raised the entrance fee daily by requiring more pulls earlier the door would open up, until each animal had paid its maximum price and ended its visit to the bedroom.

Figure 2

An operant technique using the "maximum toll approach" measured the forcefulness of motivation for social contact vs. food in silver foxes. Each fox delivered increasing numbers of pulls on a loop cord for access to food, the baseline resource. Numbers were compared to the corporeality of pulling that the same animals delivered for access to a companion.

The researchers could now work out the average price the juvenile foxes were willing to pay for each resource. Food was the most desired commodity with an average of 1632 pulls betwixt the six females (min 224, max 2368). However, the cost paid for social contact averaged every bit much as 512 pulls (min 128, max 992), which represented 38% of the value that the foxes placed on food when hungry. Thus, the researchers concluded that female silver foxes do desire social contact as juveniles (Hovland et al. 2008).

Such operant experiments, relying on simple behavioral responses that allow animals to show us what they want, can give valuable insight into resources that are important for animate being well-existence.

Example Study 2: Food Preference and the Physiology of Choice Beliefs

Amid dearest bees (Apis mellifera), individuals participate in social food-gathering exterior the colony. Some bees prefer protein-containing pollen from flowering plants, while others seek out nectar — a rich source of carbohydrates. Bees with different foraging preferences also bear witness different expression-levels of insulin-sensing genes in their abdominal fat (Amdam & Page 2010). Insulin sensing is active in muscles, liver and fat during uptake of saccharide (glucose) from the blood, but insulin signals tin can also human action remotely on the brain to regulate eating behavior (Vettor et al. 2002).

How tin we examination whether insulin-sensing genes in the bees' abdominal fatty can act remotely on the brain, to affect behavioral preferences toward pollen and nectar collection?

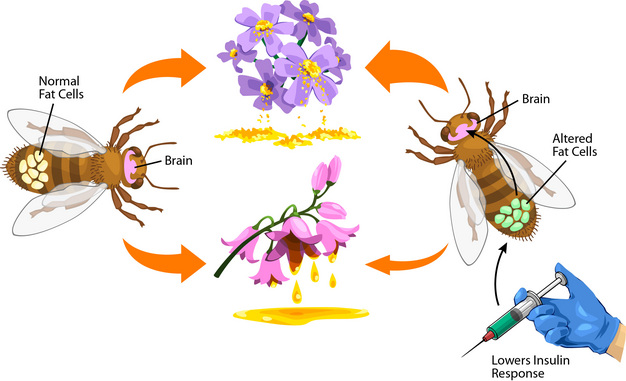

Genetic effects on behavior tin be studied in laboratory animals where the genes of involvement are "knocked down", and then their expression is disrupted. Like factor knockdown can exist achieved in the abdominal fat cells of dearest bees with a technique called RNA interference. Using RNA interference, scientists compared 150 knockdown love bees toward a reference group with a similar number of control bees. The controls went through a matching technical and biochemical handling-procedure that did not cause factor knockdown. The knockdown treatment targeted IRS (the Insulin Receptor Substrate); a cistron that is central to insulin sensing. The knockdown and control bees were tagged, transferred to honey bee colonies, and carefully observed. Tagged bees were captured when returning to their host colonies from foraging flights, and the researchers measured their gustatory (taste) response to sugar equally well as how much pollen and nectar the bees collected (for more than details, see Wang et al. 2010).

The scientists plant that the handling and control bees responded equally to sugar, but the IRS knockdown bees collected almost xxx% less nectar and proportionally more pollen than the controls. The report ended that an insulin-sensing gene in the abdominal fat of honey bees could influence the insects' foraging choice-beliefs without altering the bees' taste for sugar (Wang et al. 2010).

Effigy 3

By reducing insulin sensing in abdominal fat cells of love bees, scientists revealed a function of these cells in food-option beliefs. After a central factor in insulin sensing was knocked down (Altered Fat Cells), the bees abased sugar-containing nectar in favor of protein-rich pollen. The control group (left) received equivalent technical and biochemical treatment but retained normal fat cells.

Such basic experiments on how physiology can bias individuals toward unlike food cravings can help our progress in understanding food-related beliefs and how it influences man health.

Glossary

Adaptive behavior – Any behavior that enables an beast to accommodate to a specific situation or environment, and that supports the animal'due south long-term survival and reproduction.

Ad libitum beliefs sampling – To record all instances of beliefs that seem appropriate in an animal or in groups of animals. Requires no specific rules for how the behavior is recorded or which animals are recorded.

Decision-making – To evaluate the perceived stimulus and select an appropriate behavioral response. The process of decision-making tin can be simple (e.grand., rely on sensory filters), or involve complex cognitive processes like problem-solving.

Experimental controls – Subjects that do not receive experimental treatment but are similar to treated subjects in all other respects.

Experimental paradigm – Established methods that let experiments to be conducted by specific standards. Typically rely on theory that guides methods-development and use.

Operant response – A learned beliefs established based on the consequences of its functioning.

RNA interference – Enzymatic cleavage of an mRNA based on its recognition by the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Recognition uses a short template RNA in RISC that is complimentary to a segment of the target mRNA sequence. RISC-mediate cleavage of mRNA can silence gene expression by reducing the corporeality of mRNA available for protein synthesis.

References and Recommended Reading

Akre, A. K., Bakken, K., & Hovland, A. L. 2009. Social preferences in farmed silver play a trick on females (Vulpes vulpes): Does it alter with age? Practical Animal Behaviour Science 120, 186–191 (2009).

Amdam, Thousand. V. & Page, R. E. The developmental genetics and physiology of honeybee societies. Animal Behaviour 79, 973–980 (2010).

Frison, G. C. Paleoindian large mammal hunters on the plains of North America. Proceedings of the National University of Sciences of the United States of America 95, 14576–14583 (1998).

Goodall, J. Nest building behavior in free ranging chimpanzee. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 102, 455–467 (1962).

Hovland, A. L. et al. The nature and strength of social motivations in immature farmed silvery fox vixens. Applied Animal Behaviour Scientific discipline 111, 357–372 (2008).

Jackson, R. Due east., Waran, Northward. G., & Cockram, Thou. S. Methods for measuring feeding motivation in sheep. Animal Welfare eight, 53–63 (1999).

Kirkden, R. D. & Pajor, Eastward. A. Using preference, motivation and disfavor exam to enquire scientific questions nigh animals' feelings. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 100, 29–47 (2006).

Real, L. A. Brute option behavior and the evolution of cognitive architecture. Science 253, 980–986 (1991).

Vettor, R. et al. Neuroendocrine regulation of eating behavior. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 25, 836–854 (2002).

Wang, Y. et al. Down-regulation of honey bee IRS factor biases behavior toward food rich in protein. PLoS Genetics 6:e1000896 (2010).

Zeder M. A. Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: Origins, diffusion, and impact. Proceedings of the National University of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 11597–11604 (2008).

Source: https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/measuring-animal-preferences-and-choice-behavior-23590718/

Posted by: mclachlanlaze1999.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Do Researchers Measure Animal Behavior Using Their Perspective"

Post a Comment